MORE OLDER INFORMATION ON CERN CALLING IT “MAGNETORRESISTANCE” YES! NOW WE ALL KNOW CERN IS EVIL AND AGAINST GOD. USED TO MESS WITH ATOMS, STRANGELET BOMBS AND THE EARTHS MAGNETICS. IT IS AND ALWAYS WAS TOTALLY ILLUMINATI PROJECTS FOR THE REPTILIANS TO SCAB OUR MONEY FROM TAXES – THROUGH THE VATICAN AS THEY STEAL OURS AND OTHER THINGS THEY ARE DOING AS THE REPTILES WANTS TO CONQUER! THEY ARE REAL PROUD OF THEMSELVES WANTING TO DESTROY US & EARTH! THEY HAVE BUILT A JET FUSION REACTOR IN OXFORDSHIRE ENGLAND. WAKE-UP WORLD BEFORE THERE IS NOTHING LEFT OF US. THE DEMONIC IDIOTS RUNNING AND RUINING OUR PLANET SEEM TO HAVE BUILT ANOTHER CERN?

Energy

Energy is an essential and expensive component of modern life, and how we generate it has huge effects on the environment. Our limited current investment in energy research doesn’t reflect the importance of improving it.

Civilisation depends on its supply of energy to function: we in the UK spend around £2200 per capita fuelling our cars, homes and factories. Energy research, by comparison, receives around £10 per person per year. That’s less than 0.5% of energy spending.

There’s a pretty strong economic case for scientific research into energy sources: the UK’s per capita energy spend has increased from £1300 per capita in 1997 to £2200 in 2011. This 60% increase has been driven largely by factors beyond our control: we depend on fuels whose prices are highly volatile due to global supply and demand, and market speculation. If we’re confident that science can make our energy even 0.5% cheaper in the long run, it’s worth investing significantly more than the £10 we do at present.

In addition, the fossil fuels that provide the majority of our energy are both finite, and damaging to the environment. To avoid dangerous (and expensive) climate change, we need to find new ways to either generate power without emitting carbon dioxide or sequester the carbon dioxide we do emit. These new or improved power sources will be made cheaper and more efficient through scientific research.

Nuclear fusion

To focus on one technology in particular, we spend £1.20 per capita—a mere 0.05% of our spend on energy—researching nuclear fusion. Fusion is a potential source of near-infinite, pollution-free energy, and the principles have already been proved. The JET experiment, based in Oxfordshire, has successfully generated 16 MW of power from fusion…albeit for less than a second. How far away is practicable nuclear fusion for electricity production? Cynics often joke that it has been thirty years away for the last thirty years—perhaps, however, given that the worldwide fusion budget is less than $1 per person per year, that’s not such a surprise.

Rather than a number of years, it makes more sense to think of fusion as a number of pounds, dollars or person-years’ work away: the more we invest in nuclear fusion now, the sooner we’ll crack it.

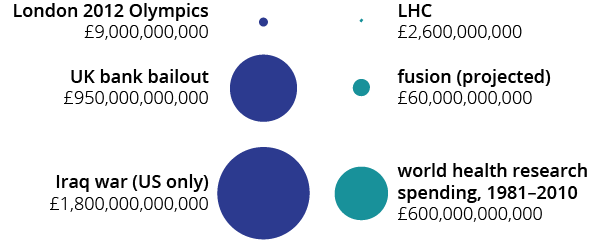

Whilst no number of experiments can guarantee that fusion will be able to generate affordable electricity, we do have a plan. The next big project in fusion research is a massive, collaborative experimental reactor called ITER, which has a budget of £13 billion, and should be showing results by the mid-2020s. This will be followed up by a similar scale reactor, called DEMO, designed to use the technology from ITER to actually generate electricity. ITER and DEMO will require other scientific support; for example, we need to test the new materials needed for long-term use inside a fusion reactor. Assuming all of this goes to plan, we could have nuclear fusion working after investing about £60 billion.

Though that might sound like an unimaginable quantity of cash, there are also a lot of people in the world: the population of the ‘high-income countries’ is just over 1.1 billion. This means we could develop fusion with a one-off payment of £50 each. In fact, the ITER collaboration represents over half of the world’s population, meaning it could be even cheaper than that: around £16 per head. It’s probably fairer if the rich countries pay a larger share of that, but still: I’d put my £50 on the table right now.

Of course, it’s not quite as simple as that: if a huge international collaboration clubbed together and wrote fusion researchers a cheque for £60 billion, we couldn’t have fusion next week; it would take time to build the labs, train new scientists to work in them and do the experiments to find out what works. But there’s a pretty compelling case that more investment would bring the results in faster. Plus, that means we don’t even need to pay that £50 each in one hit: we get a few years to scrape it together. (For more on making sense of the cost of large research projects, see the Big science page.)

Understanding fusion and developing it into a power source has only been possible thanks to foundations laid by nuclear physics and astrophysics, and we turn to this ‘blue-skies research’ in the next section.

Blue-skies research

Research with obvious, short-term applications such as that in energy and health is underpinned by a vibrant base in blue-skies research.

This kind of research is not necessarily driven by a specific goal, but is simply exploratory: scientists aim to understand the world around them, and tend to stumble across all manner of interesting and applicable surprises along the way.

It’s vitally important that we fund this so-called ‘basic’ research, but it’s much harder to draw catchy comparisons between the investment we make and the size of the objectives scientists are aiming for—often because, in the curiosity-driven world of blue-skies science, there aren’t any objectives other than understanding itself.

A high-profile contemporary example of blue-skies research is the Large Hadron Collider, or LHC, at CERN in Switzerland. It’s the largest scientific experiment ever built, an incredible engineering feat which accelerates protons to 99.999999% the speed of light—very nearly the fastest it’s possible to go—to probe the inner structure of matter and understand the fundamental workings of the Universe. Indeed, 2012 saw the discovery of a particle called the Higgs boson which explains why other particles like electrons have mass. This confirmed a theoretical prediction made in the 1960s, and won Peter Higgs and François Englert the 2013 Nobel prize.

This kind of fundamental research may sound intellectually decadent, but the LHC’s predecessor accelerators have been responsible for a variety of spin-out technologies, from health physics to microchip manufacture. In fact, if it weren’t for scientists at CERN, you might not be reading this at all—the lab provided the setting, in 1989, for the development of the World Wide Web. This is the kind of totally unforeseen spin-out we sometimes get from basic science: CERN’s high concentration of bright people and networked computers just happened to be in the right place at the right time. But when you write a grant application to investigate some obscure aspect of the nature of the Universe, it would be pretty bizarre to write ‘one in a million chance of revolutionising society’, even though that chance is implicit in many basic research projects.

Whilst we can’t be sure what application discoveries made at the LHC may have, the UK subscription to CERN sets us back just £1.50 per person per year; almost the same as the amount we spend on peanuts. In other words, discovering the Higgs boson literally cost peanuts. With the potential for hugely significant, totally unforeseen discoveries from a project at the cutting edge of our understanding of the Universe, this seems like a bargain.

The riposte from scientists working on renewable energy (which receives only a little more public funding than CERN), or stroke (at 37p per person per year), might be to observe that their fields too cost peanuts, but have very concrete applications. The answer here is surely not to cut funding the LHC—it’s to devote additional funding to those other areas. We have no idea what the cost would be of not learning what the LHC will go on to discover, so we’re each effectively buying a lottery ticket a year to fund CERN—except it’s a much more interesting gamble, with far better odds.

Unexpected discoveries

The LHC follows an illustrious heritage of projects with no specific social goal which have resulted in technologies which are all around us. Below are three examples that were extremely scientifically significant—all three resulted in a Nobel Prize for their discoverers—but have had an even more significant, unpredictable impact on our everyday lives.

Lasers

Developed in the early 1960s, lasers started out as a scientific curiosity, but their inventors could never have dreamed of their huge range of applications: from laser eye surgery in medicine to laser cutting in industry; from barcode scanners in supermarkets to DVD players and laser printers in homes and offices.

Antibiotics

The serendipitous discovery of penicillin, the world’s first antibiotic, is so well-known as to be almost cliché: Alexander Fleming, a Scottish biologist, noticed that bacteria weren’t growing in a small halo around some mould which had contaminated one of his samples. When the substance the fungus secreted was isolated, it turned out to be highly toxic to bacteria but largely harmless to humans. It wasn’t previously known that antibiotics even existed, but penicillin and subsequent antimicrobial drugs have saved millions of lives.

Giant magnetoresistance

In 1988, separate research groups in Germany and France observed a strange effect when dealing with very thin layers of magnetic materials: depending on their relative direction of magnetic alignment, it became significantly easier or more difficult for an electrical current to pass through them. This was an exciting piece of new physics, and earned its co-discoverers the 2007 Nobel Prize in Physics. However, technology moves faster than the Nobel Prize committee; it was a decade earlier that materials exhibiting this effect had found their way into hard disk drives…and they’re still there; if you’re reading this on a computer, it’s probably making use of this effect right now.

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/2007/

The Nobel Prize in Physics 2007

The Scienceogram

This is the Scienceogram: our one-page précis of UK science spending.

It gives an overview of how investment in science compares to the size of the problems it’s seeking to solve. If you want more detail, check out the In depth pages for further information.

Government spending

The UK government spent £695 billion on our behalf last year. This is a mind-bogglingly enormous amount of cash and so, to try to make sense of government spending, we’ve divided it up into pounds per person per year. The government spends about £11,000 a year on behalf of each person in the UK. Big-ticket items include pensions and benefits, health, education and defence, and we spend £160—about 1.5%—on science.

Health

Cancer kills nearly a third of us, and yet public spending on cancer research is less than £5 per person per year. Heart disease is responsible for 15% of deaths, and receives £1.30 per person per year, and stroke is responsible for another 10% and gets just 28 pence!

Energy

We spend around £2200 per capita fuelling our cars, homes and lifestyles, whilst spending around £10 per capita—less than 0.5%—looking into ways to make energy production cheaper and greener. Of this, we spend just £1.20 per person per year researching nuclear fusion: a source of near-infinite, clean energy. If we want fusion any time soon, it’s worth more than 0.05% of the energy budget.

Big science

Acquiring knowledge is an international, collaborative endeavour, and it’s only acquired if we try. It’s common to think of scientific breakthroughs as a number of years away, but it makes more sense to think of us as being a number of person-hours, or a certain investment, away from the next giant leap. When compared to other items of international spending, science looks very cheap…and those discoveries look tantalisingly close.

Get involved

Convinced we should spend more on science? We at Scienceogram HQ are trying to get the word out. Why not follow us on Twitter or Facebook, or tell your MP what you think? Or, go the whole hog: want to create a Scienceogram for your country?

The cost of space missions

This week, NASA’s New Horizons probe made the first ever flyby of distant, frozen Pluto. We were wondering how much the mission cost, how that stacked up against the price of other space exploration, and how that looked in context with other expenditure…in this case, the war in Iraq. We’ve produced an infographic to try to make sense of it all. Please share it!

The basic take-home message here is that space exploration is cheap: an ambitious space mission might cost a couple of billion dollars, which is a few dollars per American, or euros per European. As our Rosetta infographic points out, it’s also important to remember that these costs are spread out over the duration of the mission, which is often a decade or more. That means exploring space costs literally cents per person per year, for which we get spectacular images, important science, and the ever-present possibility of spin-out technologies which can transform our everyday lives.

By comparison, the war in Iraq is estimated to have cost the US alone three trillion dollars. We had to divide that up into a per month cost just to get it to fit on the graphic, and even then it dwarfs the cost of space science. Sending New Horizons to Pluto cost less than an average day in Iraq.

Each of these missions is fascinating in its own right, so do read more about Voyager, Curiosity, Rosetta and Dawn. But of course the limelight at the moment is firmly on New Horizons as the first high-resolution images of Pluto’s mysterious surface trickle back to Earth. Massive congratulations to the team!

******************************************************************************

FROM THE FIRST ORDER;

MY GUESS IS THIS PROGRAM IS LOOKING FOR EVEN MORE MONEY AS THE ILLUMINATI IS TRYING TO SCAB MONEY EVERYWHERE, AS THEY STILL THINK IN THEIR SICK AND TWISTED MINDS, THAT THEY WILL BEAT GOD USING THE CERN. UNBELIVABLE. THE CERN WAS BUILT TO DESTROY THE ATMOSPHERE AND TO SCREW AROUND WITH ATOMS AND THE MAGNETICS OF EARTH! BY THE WAY THAT IS NOT THE FULL STORY OF PLUTO. THEY ARE HIDING IT!

NOW THEY WANT THE ILLUMINATI APPLE PRODUCTS TO PAY FOR CERN AND COLD FUSION, WHAT ELSE IS NEW. ONE MONOPOLY AIDING THE REPTILES! YOU KNOW THAT MONEY WILL GO TOWARDS KILLING US OR THE CERN ETC.

******************************************************************************

http://scienceogram.org/2015/02/apple-record-profits-nuclear-fusion/

Apple’s annual profits could pay for fusion

At Scienceogram, we’re used to looking at massive numbers in the context of government spending. However, this week the most talked-about figure has come from the world of commerce:Apple’s record-breaking profits.

The firm announced that the popularity of the iPhone 6 had contributed to quarterly profits of $18bn, or around £12bn, the largest ever recorded for a public company. If this performance continues, Apple could afford to develop nuclear fusion by the middle of next year. And then do it again in 2017, and again the year after that.

Nuclear fusion is the energy source which powers the Sun and, with further research, could provide an essentially infinite source of carbon-free electricity. Scientists think it would cost around $80bn (£60bn) to go from the experimental reactors we have now to commercially viable power stations. This compares to Apple’s profits in the financial year to September 2014 of just under $70bn (£50bn).

There are, of course, many other worthy scientific projects in energy research and elsewhere that could benefit from this level of investment. Also, there are many other highly profitable public companies: what this comparison really illustrates is that science, compared to many of the figures floating around in the private sector, can be surprisingly cheap.

For a more in-depth analysis of big figures in research and elsewhere, check out our big science page.